This post has been coming for quite a while. I have mulled over it, slowly editing, transcribing, and cleaning up what I have found for publication from an old microfiche file. The events blogged about earlier this week (the sexual assault lawsuit against Thomas Rosica and the victim's gall, through his solicitor, to seek this writer as a witness) have caused me to consider it again. Therefore, I have made the decision to publish what follows.

The purpose of this publication is to document an occurrence forty years ago and provide a historical record of certain activities at St. Augustine's Seminary in the Archdiocese of Toronto and the corruption of the times, the power and influence from the 1980s which are still being felt today. One of the priests featured below is retired, yet, as recently as a few months ago, remained on the Archdiocesan Priests Council. This is not an accusation of anything untoward on the part of the new Archbishop, now Cardinal Francis Leo, Indeed, this history may likely be news even to him and if this provides any service to him, to know the history and the rot and expose those who have worked against the faith, then that alone is worth its publication. The Catholic faithful of the Archdiocese of Toronto have a right to be aware of things that happened forty years ago that have long been forgotten or covered up and still affect the Church today. Many think that we have had no crisis of sexual perversion or abuse. This is not true. What we have is enough money to buy off the victims and force them into signing non-disclosure agreements.

Let me raise some points of fact, about the hushed up scandals that happened here in the Archdiocese of Toronto:

- A certain highly placed cleric, a Monsignor, in the chancery, fathered at least two children whilst in his high clerical office of Chancellor of Spiritual Affairs and Vicar General. What became of the mother? He went on to become a successful financial executive and passed away in 2022.

- A priest professor at St. Augustine's Seminary raped and sodomized a young seminarian so badly that he was taken away by ambulance to repair the anal rupture. Years before, the Cardinal at the time, Aloysius Ambrozic, was told to get rid of him, to which he responded. "I have nobody else to teach liturgy." That injured seminarian was later ordained in the United States where he remains in a religious order. He was ordained by a Toronto Auxiliary Bishop in Washington. Odd, no? Police were not called. Charges were not laid. The crime was never reported. It was covered up. The perpetrator is now dead and judged.

- That same priest professor in a former post as a religious order prior was a pastor in a Mississauga (west of Toronto) parish and could very well be responsible for at least two other priests he may have "groomed." One of these is an openly homosexual man who left the priesthood, played the piano as a lounge singer, married a woman, divorced her and now lives in a same-sex relationship with another man. The other, whose theology and priestly formation skills were warped by the 1960s and the radical and false "spirit of Vatican II", was, in 1976, Toronto's own James Martin of his day. He rose to rank as Rector of St. Augustine's and later Judicial Vicar. You will read about him below. Both of these men were formed as youth or young priests under that same Friar in Mississauga.

- A certain "hunk" of a Monsignor with the same Irish surname as a then Toronto Police Chief was frequently brought home to the Rosedale mansion of Cardinal Carter, "daddy," drunk and in drag from the gay district on Church Street.

- Another priest professor at the seminary was known to fondle young men and worse and was found coming out of the St. Charles Tavern on Toronto's Yonge Street and bragging about it in secular media.

- Several deaths of priests and professors from AIDS.

In the photo of a book page above, the late Anne Roche Muggeridge refers to a document called, "A Dialogue of Trust." It was written by the then Rector referred to above, who was fired for it, sent away to the Catholic University of America in Washington to study and then returned to the Archdiocese of Toronto and served at a senior level in the chancery structure as the Judicial Vicar. All true. He kept the keys to the vault on matters such as lawsuits, assaults and abuse. As referred to earlier, as of a few months ago, he still remained on the priests' council. As a point of personal reference, I actually attended his first Mass at St. Domenic's in Mississauga. My father was the family barber.

These crimes and abuses happened in the age before the internet and search engines. The money of the Archdiocese silenced who it had to and forced non-disclosure agreements upon them. Stories abound about car accidents and bicycle accident deaths, one in particular of a prominent priest, but none can be proven. All of the information above has been given to me by priests of the Archdiocese of Toronto. They know. Some know more than others. All has been covered up and all the names are known. As for the letter referred to by Anne Roche Muggeridge, nobody had a copy of "A Dialogue of Trust." It disappeared into history, it was never written, it didn't exist, nobody had it, and it was not published and could not be found. Until now.

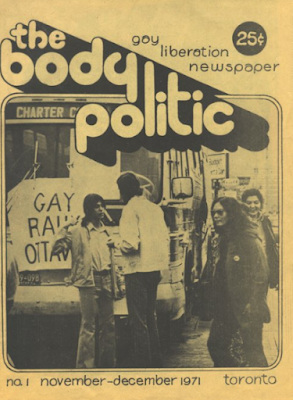

The Body Politic was a "gay" newspaper published monthly and founded in 1971 until it ceased publication in 1987. It was located on Yonge Street not far from that same St. Charles Tavern where the academic priest abuser hung out. After intensive searching, "A Dialogue of Trust" was found. It had been published in The Body Politic as part of a larger article on the attempt by Gerald Emmett Cardinal Carter to "hide his gay purge" of St. Augustine's Seminary. It makes one ask, if not for the intrepid reporters at The Globe and Mail back then, certainly not on the side of the Church or Seminary, what would have happened? Would we have ever known? If all of those events above occurred under the administration of Cardinals Carter and Ambrozic how much worse would it have been without the reporting. It seems that after Cardinal Carter's "purge," only two seminarians left. What of the others? How many went on after 1983 to be ordained and were men who had or may have continued to act out their same-sex desires and attractions ordained and what has it meant for the Church in Toronto? How many of their mentors are still around to influence the Church in Toronto. Again, I repeat, part of the purpose of this post is as a public service to Archbishop Leo.What follows was transcribed from a microfiche copy by the writer. Bear in mind, that it was written for an audience sympathetic to the cause.

TORONTO'S ARCHBISHOP TRIES TO HIDE HIS GAY PURGE, BUT THE STORY GETS OUT

Cardinal slams the closet door

Tensions over the apparent presence of gay students in a seminary in Metropolitan Toronto have escalated, with the help of Gerald Emmett Cardinal Carter, into an anti-homosexual witch-hunt which has led to the dismissal of three faculty members and the expulsion of two students.

Some details of the purge at St Augustine's Seminary in Scarborough, the preeminent school for the training of Roman Catholic priests in English-speaking Canada, were made public in two reports published by The Globe and Mail on September 7 and 8. The stories said that the Rev Brian Clough, St Augustine's rector, and the Rev Thomas Dailey, dean of studies, had been dismissed the first week of June and that the Rev John Tulk, a professor of church history, had been fired early in September.

Globe reporters Stanley Oziewicz and Peter Moon uncovered the following facts:

• Carter, the archbishop of Toronto, ordered the dismissals after an investigation of the seminary conducted at his request by the Most Rev Marcel Gervais, auxiliary bishop of London, Ontario;

• Carter asked Gervais to investigate after coming into possession of a document about "tensions" between gay and straight seminarians that was distributed to St Augustine's sisters, students and faculty by Clough;

• The tensions had arisen from allegations of homosexual behaviour at a party held in Tulk's rooms at the seminary.

Beyond these few facts, little has been revealed about the origins of the dispute. Although he had reported the June dismissals when they occurred, Oziewicz first learned some of the details several weeks later from an anonymous letter. In their September stories, Oziewicz and Moon wrote: "Sources, including members of the faculty and student body at the seminary, members of religious orders and laymen, agreed to talk for this article provided they were not identified. Many feared for their future careers if their names were used...." TBP's own investigation has encountered similar fears. Most of those interviewed said they feared retaliation by Cardinal Carter. A priest told TBP: "The diocese is actively trying to find out who gave that information to The Globe and Mail." A member of a religious order commented: "He (Carter) doesn't show any sensitivity toward people, so they're afraid to speak out." When told TOP had been able to learn much of the story and would publish it, the member added, "It will do a lot of good because it shows how they really operate."

In addition to those quoted, TBP's account of the tensions leading to the dismissals and expulsions has been gathered from a well-placed source who wishes to remain anonymous, and from documents which have come into our possession. Brian Clough could not be reached for comment. A copy of this article was sent to Margaret Long, Assistant to the Director of Communications of the Archdiocese of Toronto, for comment, but she did not return any of TBP's calls.

Cardinal Carter: a secret operation against creeping Protestantism and homosexuality

The presence of suspected gay students in the seminary apparently first became an issue during the 1982/83 seminary year when some first-year students complained about the campy behaviour of some other students. The issue was taken up by an informal group of about a dozen conservative seminarians who were united by their dissatisfaction with the faculty's generally liberal interpretation of Catholic theology. They came to be known as "the machos." Defenders of those accused were dubbed "the effeminates," the group to which the two students who were expelled belonged. Most students belonged to neither. (According to Oziewicz and Moon, Gervais found that between six and 12 of the approximately 50 students were "homosexually oriented." Our source suggests that even Gervais's upper figure may be much too low.)

Gossip and paranoia flourished. Dennis Hayes, a seminarian who says he belonged to neither group, explained: "When you group a number of people you have a fishbowl type of effect; when people start talking, these things spread.. an innocent comment can turn into a vicious attack."

In March 1983 several students were criticized in their written year-end evaluation by faculty for their "feminine mannerisms."

A month later, the authors of an annual letter from students to faculty complained that the faculty was tolerating a "vigilante group" that was harassing suspected gay students. The letter also said that criticism of some students for their mannerisms had exacerbated the situation.

By September it appeared that the letter had had some effect: at the week-long retreat which starts the school year, most of the faculty who spoke of the matter called for tolerance of differences in the seminary.

But the complaints continued. Charles Lewis, a former RCMP employee said to be in the "macho group" — an allegation which he did not deny — told TBP he himself had lodged a complaint about sexual activity in the seminary: "guys doing things they shouldn't be doing." But he admitted he hadn't witnessed such activity himself. On the other side, rumours flew that "the machos" were searching

Toronto's gay bars for seminarians.

TBP has found no evidence to support this allegation.

Tensions between the two factions became so acute that, in the late fall, Clough held separate meetings with members of the two groups and with unaligned students in an attempt to cool the dispute.

But after a party held in Tulk's rooms following a joint religious service with Anglican seminarians on January 26 of this year, events started to spiral out of control. Although Gervais later was to find that nothing amiss had occurred at the party, rumours circulated of drunkenness and homosexual activity.

In a speech delivered to St Augustine's seminarians at a special house meeting six days later, Clough criticized "the rumour mill" and appealed for an end to gossip about the party. On February 8 he met again with members of the factions and other students, this time in a joint meeting.

Then, on March 19, a three-page letter, "A Dialogue in Trust," apparently written by someone who had been at the February meeting, was distributed on Clough's authority to the seminary's students, faculty and sisters.

Compassion and the Cardinal

The Archbishop of Toronto knows how to pick friends, and if you're not one of them. . . .

"CARDINAL CARTER AIDS DAVIS: No Solidarnosc for T.T.C. Workers" — that was the heading on a leaflet twitting Gerald Emmett Cardinal Carter, archbishop of Toronto, for backing strikes in Poland while opposing a threatened transit strike at home that would have cut into attendance at, and profits from, the recent papal tour.

Carter, a close friend of John Paul II, was a supporter of the Second Vatican Council, which reformed the Catholic Church. Yet, his critics say, Carter is more zealous for the letter of the reforms than for their spirit. Last year, when the Canadian Council of Catholic Bishops issued an economic report that blamed the profit motive for widespread poverty and unemployment, Carter disavowed the document, siding with the outraged bankers and industrialists. And early this year he authored a pastoral letter which condemned attempts to elaborate a Catholic theology that would allow birth control, abortion and the ordination of women.

Carter's record on gay issues is not completely black. He once wrote a report on police/minority relations which devoted a few lines of criticism to homophobic verbal abuse. But he has also barred the local chapter of Dignity, the gay Catholic organization, from the use of a church for their meetings and has told homophobic jokes to an audience of police officers. The fear and silence surrounding the purge at St Augustine's Seminary point not just to the man's power, but to the way he exercises it. "Insensitive" is the word which most often comes to the lips of his critics. But Carter may have inadvertently illuminated the issue when he dismissed Thomas Dailey. According to the press reports, he told the priest, "You are much too compassionate." Perhaps it is not others, who are too compassionate, but the Cardinal who is not compassionate enough. Although unsigned, the names of Clough and three students appeared at the bottom of the letter. A notable feature of this letter is its twice-stated concern that news of the tensions within the seminary might get beyond its walls. The fearful reference to "having 'outsiders' resolve those issues for us" appears to have been an allusion to Cardinal Carter.

"A Dialogue in Trust" proved to be the means of betrayal: within a few days, a copy had been conveyed to Carter. And by the second week of April, Gervais had begun his investigation into theological and sexual deviation at St Augustine's.

In the purge of St Augustine's, a harmonious constellation of authoritarianism, sectarianism and homophobia can be seen at work. Since the Second Vatican Council, part of the Catholic clergy and laity have been moving away from both the church's traditional insistence on authority as the source of truth and the concomitant paranoia about Protestant theologies. The council suggested that truth is not absolute, that a changing world can pose new questions and demand new answers.

St Augustine's Seminary has been influenced by this new current in Catholicism and has exposed its students to the interaction of social activism and feminism with traditional teachings. As one of the eight theological colleges that jointly make up the Toronto School of Theology, an ecumenical project, the seminary has encouraged an open-minded comparison of Protestant and Catholic beliefs.

But as the new Catholicism has developed, so has the conviction among some Catholics that the revolt against authority and the flirtation with Protestantism — often the same thing to their eyes — have gone too far. It is common knowledge in the Diocese of Toronto that Cardinal Carter and other conservatives are less than fond of St Augustine's, where the now thin trickle of future priests — the seminary's approximately 50 students rattle about in a building that could hold 200 — are thought to be in danger of contamination by rebellion and creeping Protestantism. Once Carter had indisputable evidence that the place of homosexuals in the priesthood was, however informally and tentatively, being explored at the seminary, he struck.

The purge was carried out in a secrecy induced by fear: everyone who knew, even the victims, was too intimidated to speak out. To this day, Carter refuses to say why the firings occurred. Gervais's report remains a secret.

According to the Globe, although Clough, Tulk and the tenured Dailey were instructors at the Toronto School of Theology, the Cardinal ordered them to resign without any explanation to the school. Carter told TST officials that any protest from them over his neglect of due process could result in the withdrawal of St Augustine's from the joint project.

Some of the homophobia was blatant. Gervais is reported to have asked students about homosexual activity, but not about heterosexual activity. And he told faculty they should not admit gay students to the seminary. When the teachers protested that there is nothing in the rules about the sexual orientation of priests, he backed off slightly but still insisted that a gay seminarian would have to have been chaste for five years before admission. Apparently, he made no such stipulation for heterosexual applicants.

But to speak of discrimination is merely to scratch the surface; the homophobia here is deeper and subtler than that.

A trust betrayed The confidential dialogue that didn’t stay confidential

What follows is the complete, unedited text of ' 'A Dialogue in Trust, ' ' the letter circulated by St . Augustine's Seminary Rector Brian Clough to students and faculty on March 19, of this year. (1983)

The following are reflections on discussions that occurred during the past year in regard to issues and tensions that were present in the house. These discussions were alluded to in Fr. Clough's address to the house in February. Initially, Fr. Clough met with three distinct groups composed of second, third, and fourth-year students. These groups represented different viewpoints on tensions that were growing within the first few months of the seminary year. The three distinct meetings allowed students to articulate their perceptions of what was occurring within and between emerging factions. These meetings were completed by the end of the first term. A collective meeting of the three groups took place a week after Fr. Clough's February address.

The purpose of the collective meeting was to provide a forum for dialogue and for the definition of issues that each group perceived. A second issue was to receive feedback on Fr. Cough's February intervention in regard to the house social with Trinity College. It was hoped that the meeting would be an initial step toward resolution of various problems. The meeting began with an attempt to identify what the problems were. The general consensus was that there was misunderstanding of viewpoints, attitudes, and behaviors. This was characteristic of all, not of a certain few. It was recognised that many of us did not know each other well enough and were unsure about positions held, which generated unease and, perhaps, a little suspicion. Within an institution there will be a broad range of personalities and attitudes. Such a situation can all too easily lead to conflict, which itself produces intolerance and insensitivity. It was felt that we were categorizing each other as to lifestyle and orientation. It should be noted that in Fr. Clough's February address there was mention made of a general nosiness of other's business and a consequent breakdown in trust. The problem, then, was one of misunderstanding and unfamiliarity that led to insensitivity and intolerance. Discussion ensued with each group expressing its feelings on the problem. It was felt that each group was given a free and equal opportunity to express their views. As the discussion progressed, it became evident that group boundaries were breaking down and that each was expressing his views as an individual, rather than as a representative of a group.

It became clear that the issue would be lost if the discussion were limited to the surface problem: that is, a tension between those perceived to be "macho" and those perceived to be "effeminate". It was agreed that such exclusive terms are damaging and denigrating. It is all too easy to categorize someone because he acts differently. The issue was then not how to limit those who act differently, but how to come to know the other with greater appreciation and understanding of his uniqueness.

Five main points were made during the discussion:

1: to equate homosexuality with effeminate behavior is false. A person's sexual orientation should not become a preoccupation for others. The issue is not one of homosexuality or heterosexuality within or outside the seminary, but one of sensitivity to others who may be different than ourselves.

2: it is important to be sensitive to the effect that our behavior has on others and the possible effects or perceptions that can result from the cumulative effect of group behavior in a particular situation.

3: it should be recognized that feelings of being threatened by another's uniqueness have their source within ourselves and must be resolved within ourselves. The problem should not be 'how can I change the other', but 'how can I come to terms with myself so that I can appreciate the other more'.

4: out of an ignorance of another's pain can come a desire to avoid that individual because he is different. Thus the challenge must be recognized: to confront someone with a problem is harder than not dealing with him.

5: the seminary community has a right to resolve its own issues without having them communicated outside the house or having "outsiders" resolve those issues for us.

The immediate results of the meeting were generally positive. It was felt that dialogue which occurred within the context of the meeting could be transferred to a less formal setting. Much misunderstanding was identified and corrected. It may be correct to say that tolerance was learned and that out of that learning came a greater appreciation and comfort with others who were different than ourselves: that is, a tolerance that was embedded in charity and mutual respect. With the reduction of tension through the expression of difficulties came a more relaxed atmosphere in the house. An important result was that the "silent majority" spoke-up and took an active part in the discussions. It was agreed that the meeting was an initial step to the resolution of the issue. Though the issue was not totally resolved, the meeting provided an opportunity to dialogue in trust.

The less immediate results were just as important. The meetings that occurred this year served as a first step to dialogue that can and will hopefully occur in years to come. It was recognized that there will always be problems in institutional living and that these problems should be addressed. Thus, the path was opened to future dialogue. It was suggested that the services of professionals, such as Sister Dickson, be employed in addressing issues such as sexuality, spirituality, tolerance, etc. It has been suggested that an opportunity be provided for year groups to reflect on the year with their representatives to the extended faculty meetings. It was also suggested that new students precede returning students at the start of the year by a day or two in order to better prepare them for seminary life and to ease the process of assimilation. In all, these discussions came out of an experience of grace; an experience that was felt by the whole seminary community. The meeting of the collective closed with the hope and the positive anticipation of greater interpersonal communication and friendship

19 MARCH 1984

M. CENERINI

FR. B. CLOUGH

J. MURPHY

D. REILANDER

This document has been distributed to the sisters, faculty, and students of St. Augustine's Seminary. Its purpose is specifically for the members of the house, i.e. the document is confidential to members of the house. This is why the document has not been posted on the bulletin board.

END OF A "DIALOGUE OF TRUST"

Single-sex institutions in the world.

Homosexual activity is inevitable; that a certain fraction of its members will be gay is inevitable. Yet it remains a great unspoken concern. Mary Malone, a St Augustine's faculty member, says: "The presence of gay students among seminarians is not new. Until recently, we pretended it wasn't there."

The St Augustine's purge was directed not so much against gay seminarians as against those, gay or straight, students or faculty, who dared to break the silence — to push or pull open the closet doors just a crack. The purge would be a warning to those still in the closet to stay there. That's perhaps why only two students were asked to leave the seminary, although Gervais estimated that there were as many as 12 "homosexually inclined" students there. That could be the meaning of Carter's explanation to reporters of Clough's dismissal: "To talk about it is one thing, but to put it in print (in "A Dialogue of Trust") is a problem."

Malone describes Clough and Tulk as "honest, compassionate men." "Their integrity," she says, "helped something come into the open that others would have preferred to keep secret." Clough, Dailey and Tulk are gone from St Augustine's, but those responsible failed in their goal. The secret is now out in the open.

+ + +

The Rector referred to above, Father Brian Clough, after being fired for the scandal went on to become the Judicial Vicar for the Archdiocese of Toronto. This article is from the Globe and Mail on May 8, 1976. As of a few months ago, Clough was still on the Priest's Council.